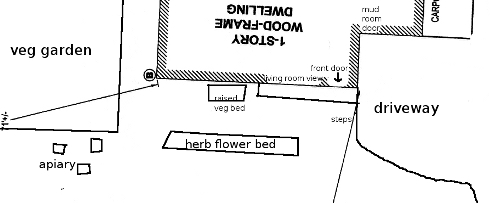

Back to patterns! Having a plan for the slope has re-opened my mind for the immediate front: the balcony, the level stretch of garden up top, the top of the driveway. This is what it looks like right now:

I already analyzed one of the more general  problems: the negativity of this space. There are some more specific patterns that can be applied, or rather, actualized here to address that. Let’s start with the patterns that apply to approaching, entering, arriving and leaving. Alexander et.al. write: “The process of arriving in a house, and leaving it, is fundamental to our daily lives” (p.554). The first pattern is this:

110. Main Entrance: Place the main entrance of the building at a point where it can be seen immediately from the main avenues of approach and give it a bold, visible shape which stands out in front of the building.

At our place the problem is not so much the lack of an obvious entrance, but a confusion between two entrances. At the moment there is only one way to approach our house, which is the driveway, and upon that approach you see the mudroom door and the “official” front door on the “balcony”.

As the “official” front door leads straight into the living room, we prefer to use the mudroom door when it is cold, rains or snows. The mudroom has room for boots, umbrellas and coats and acts like a sluice, keeping the cold out. But when it’s warm we usually leave the front door open, with a screened door that allows light into the dark corner of the living room. Needless to say, in all but the situation when there is uncleared snow on the path and the balcony steps (as in the picture), visitors are confused: which door to use? Idea:  make it so that in summer and fair weather the “official” front door seems the way to go, and that in all other situations the visitor is directed to the mudroom.

But first, what to do with each of these entrances? Â I’d like to apply to them the following three patterns:

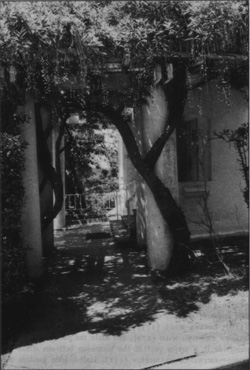

112. Entrance Transition:Â Make a transition space between the street and the front door. Bring the path which connects street and entrance through this transition space, and mark it with a change of light, of sound, of direction, a change of surface, of level, perhaps by gateways which make a change of enclosure, and above all with a change of view. Â

130. Entrance Room:Â Arriving in a building, or leaving it, you need a room to pass through, both inside the building and outside it. This is the entrance room.

160. Building Edge: A building is most often thought of as something which turns inward- towards its rooms. People do not often think of a building as something which must also be oriented toward the outside. But unless the building is oriented towards the outside, which surrounds it, as carefully and positively as towards its inside, the space around the building will be socially isolated, because you have to cross a no-man’s land to get to it. Make sure that you treat the edge of the building as a “thing”, a “place”, a zone with volume to it, not a line or interface which has no thickness. Crenelate the edge of buildings with places that invite people to stop. Make places that have depth and a covering, places to site, lean, and walk, especially at those points along the perimeter which look onto interesting outdoor life.

The mudroom fully embodies the Entrance Room pattern: it is inside the house but also feel like outside, as it is unheated and full of outdoorsy things. The visitor can’t see this, however, from the outside. In order to draw him with the promise of a Transition to the inside, we could place a trellis above the door and grow a vine on it. This would also nail Building Edge, change that transition from a mere line into a place.

The front door satisfies none of these patterns.  You walk  through and you abruptly find yourself in  the living room. This is the case in many ranches, and I don’t understand why any architect or homeowner thinks this is appropriate. It’s disconcerting for everyone!  The line between inside and outside here is filter thin, not a place at all. The tiny balcony and the roof above it are not deep enough to create volume.

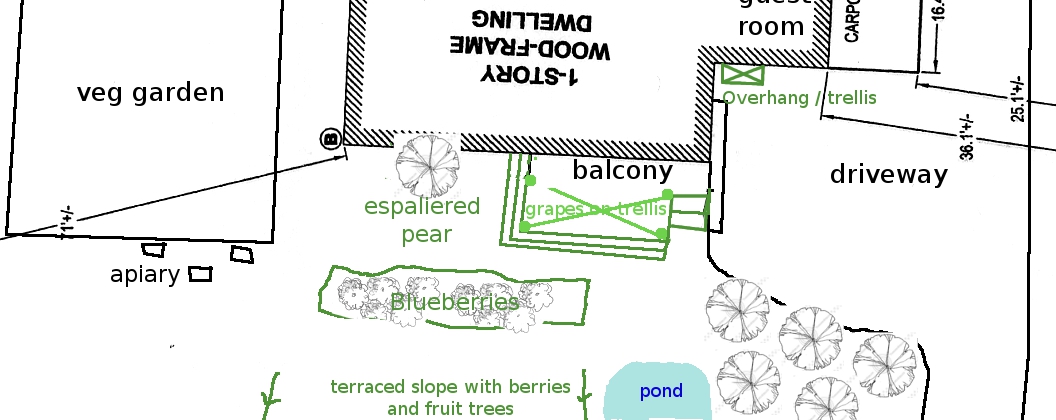

This is an area that has fantastic potential!

First let’s deepen the balcony. Alexander points out that any balcony that is less than six feet deep will not be used (Pattern 167. Six-foot balcony), and here we have an example if that. It is a mere 2 1/2 feet deep and no one ever wants to sit there. Let’s knock away the surrounding brick wall and add another five feet to the surface. Depending on what material we use, we can make it straight or rounded (think adobe!). We can forego a wall altogether and make it accessible by a step or two, all around.

But this place would be too hot in the Summer, as it’s south. So let’s make it into an Outdoor Room.

163. Outdoor Room. Build a place outdoors which has so much enclosure round it, that it takes on the feeling of a room, even though it is open to the sky. To do this, define it at the corners with columns, perhaps roof it partially with trellis or a sliding canvas roof, create “walls” around it, with fences, sitting walls, screens, hedges, or the exterior walls of the building itself.

163. Outdoor Room. Build a place outdoors which has so much enclosure round it, that it takes on the feeling of a room, even though it is open to the sky. To do this, define it at the corners with columns, perhaps roof it partially with trellis or a sliding canvas roof, create “walls” around it, with fences, sitting walls, screens, hedges, or the exterior walls of the building itself.

Let’s add a wooden pillar and beam structure around and over it, on which we grow grapes and other deciduous vines. The bare vines will allow the much needed sunlight to enter the living room in winter but the leafy canopy will shade the balcony in summer. And they grow food too (permaculture: stack functions)! The rest of the enclosure will be done with potted figs and other plants, benches, a hammock. Let’s fill this new space with all manner of places to sit, sleep, work and play in the sun, in the shade.

This will also bring to life Pattern 168, which to me is one of the most important patterns:

168. Connection to the Earth. A house feels isolated from the nature around it, unless its floors are interleaved directly with the earth that is around the house. Connect the building to the earth around it by building a series of paths and terraces and steps around the edge. Place them deliberately to make the boundary ambiguous.

This will draw us outside, to the blueberry patch, the espaliered pear tree, the path to the vegetable garden and the apiary to the right. To the left it will draw us to the pond and the dwarf orchard. To the front it will draw us to the slope with its berry bushes and trees. This is really only possible if we get that slope planted: there can be glimpses of conviviality from the street, but there must also be privacy. And even in winter it will draw us out by the eye. When standing in front of the big living room picture window, we won’t be stopped short. One more bonus: that continuation on the same level outside it will make the living room seem bigger and, depending on the material we use, it will absorb the light and heat of the sun in winter and reflect that into the living room.

Back to our original question: how to decide the visitor’s question which door to choose? When we’re done both will stand out and look inviting? I don’t have an answer yet. Maybe it will come when we look through the  patterns at the next area: the driveway and the car place.

Leave a comment