On MLK day we went to the Boston Museum of Science with friends. We mostly hung out in the Green Wing with the New England birds and natural history displays. I enjoy studying the stuffed animal skins, the skeletons and fossils in their glass cases. No doubt some of my preference is due to the old-timey-ness, the absence of moving parts, sparks, recorded voices talking at you, and screens.  The MoS unfortunately does have  computer screens and games all over the place, and for this reason I prefer  the Harvard Museum of Natural History, specifically the upper floor, where the animals, frozen behind glass, are accompanied by small labels, often even just a number.

While most visitors over and under 8 were “interacting” with the screens, I came eye-to-eye with the American Robin (Turdus migratorius) and tried to understand why I am particularly attracted to these animal skins. It’s not like they look alive. The first thing we as eye-oriented animals seek in another is engagement with the eyes, and these eyes are invariably glass or plastic. They don’t fool us. In fact, the robin’s beady eye was like a bud from which the deadness blossomed to cover the entire animal.

The kids get this right away. One of the older girls (11) said she doesn’t like to see the stuffed animals because they’re dead and that’s “creepy”. She said she likes zoos instead. I offered that I don’t like zoos so much, because the wild animals are kept in cages and I think they might be unhappy. Another computer screen distracted her, so we didn’t get a chance to hash out this live-dead/free-caged/happy-unhappy tangle together. As for myself, I’d rather see a wild animal dead than caged and that’s because death is a natural state for a wild animal (eventually), but captivity isn’t*. I value life, so what attracts me then, in these stuffed bird skins, that I’d rather spend time with them than with their with living counterparts in zoos?

***

The same question from an another angle is this: what makes the skins different from skeletons? These birds are set up, not so that they look alive, but so that we can recognize them. These specimens get to stand in, quite convincingly, for their species, a class of animals we usually don’t see in their skeletal form when they’re tearing up our garden beds in search of juicy worms. As for the specimens of New England birds I don’t recognize because I’ve not seen them (yet), I try to memorize those, so that when I see the Northern Shrike in the wetlands next time, I’ll recognize it.

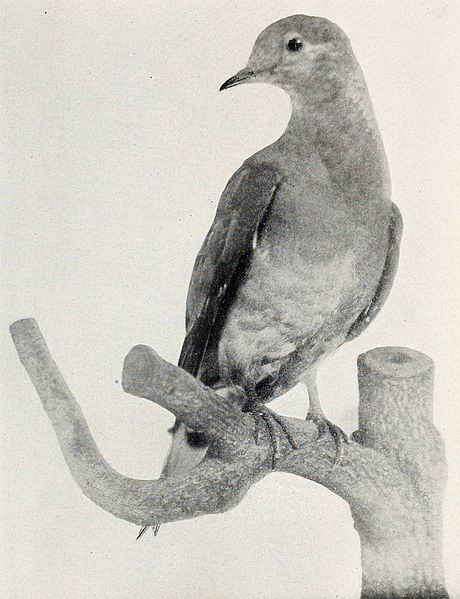

Is that the draw then, recognition? It’s part of it. To find what it is part of, there’s a test case, the case in the room that attracts me the most, the one with the extinct birds: the passenger pigeon (extinct since 1914) and, next to it, the heath hen (extinct since 1932). I look at them and part of what happens is recognition: in the passenger pigeon, I recognize the mourning dove that visits my feeders every spring. But something more happens…

Extinct. Steward Brand (TED talk) says that “extinction is a different kind of death. It’s bigger.” Who ever heard of such a thing? Let’s ask the children. Amie, when she was two-and-a-half, had repeated nightmares about a dinosaur. She woke up screaming and often would refuse to close her eyes again, because there was a dinosaur in the room, or it was coming. One evening we told her that the dinosaurs are dead. It was her first conversation about death**.

– What’s ‘dead’?

– Dead means the dinosaur can’t move, can’t walk. Dead means he can’t talk, or listen, or look. Dead means his body is lying in the ground somewhere, buried, often even crushed to pieces. So he can’t get up and come here.

– But this dinosaur isn’t dead.

– That’s not possible. All dinosaurs are dead. That’s why we name them with a special word: ‘extinct’. ‘Extinct’ means that all the dinosaurs, without exception, are dead. So no dinosaur can come here.

It was that simple:  Amie’s nightmares stopped. So clearly, extinction is a matter of quality (something different), not quantity (not just “bigger”). What makes the passenger pigeon skin different from the robin’s or the shrike’s skins might just illuminate my attraction to these bird skins.

***

Back at the museum, DH mentioned that scientists are very close to cloning or genetically manufacturing the passenger pigeon. This is called “de-extinction” and Steward Brand’s organization, Revive and Restore, mentioned in my last post, is a big part of that project. Well, I said to DH, these “revived” pigeons, they would die of fright and heartbreak. It is as for the insect egg that lies a hundred years in the soil, that by the perfect circumstance of light and temperature and humidity and ripeness bursts into life, only to find that all the plants it feeds on are long gone.

I’ll not go into my problems with Brand’s essay, “Why revive extinct species,† which reeks of smokescreens. I’ll just evoke Martha, the passenger pigeon, who was bred into captivity in 1885 in the Cincinnati Zoo, where she died, the last of her species, in 1914. Did she feel lonely? I don’t know, but for a bird that evolved and lived in flocks of over hundreds of millions of birds, her life was at the very least as unnatural as its gets, in zoos.

With Brand’s first “new” bird, we’d be back to that situation.  But, Brand and his colleagues rejoice, not for long! What happened in the past – start with five billion passenger pigeons, hunt them so there are less and less of them, down to one, then none – will be reversed - they’ll be one, then more and more and so on, one presumes, to five billion again (?).

All is reduced to quantities (extinction is a “bigger death”) and after that easily reversed simply by adding something on the other side of the equation. Nature and evolution did the work at the left side, now man will do the work on the right side. Together, they will equalize to nothing. Something will be undone. I want to stress that, that de-extinction is not about adding anything to the world, but about cancelling out, undoing something.

Undoing what? Here’s Brand, in his TED talk, asking how extinction at our hands should make us feel: “Sorrow, anger, mourning? Don’t mourn, organize.â€

Mourning is the experience of loss, a relearning of ourselves in a world where something is missing. We don’t mourn the death of a loved one, or the extinction of a species, we don’t even mourn them. We mourn their absence in our world. That is what brings us grief. Brand’s denial of mourning is therefore absolute, for he denies even the loss itself: we will not have lost, he says, it will no longer be missing.  We don’t have to mourn, we just have to make it like it never happened.

How does this reflect in the light of a story told by Weller, in the talk I referred to in my last post, of a man who asked him how he can be done with the grief for his deceased wife? Weller answers that he can’t: “This is your new relationship with your wife. This is the evidence that you chose to love.”

***

The 11-year-old who find that room at the Museum of Science “creepy” because it is full of death, gets it. The room is full of death and that is why I like it there. Because when I look at the American Robin with the plastic beads for eyes, I recognize Turdus migratorius as well as the fact that it’s dead, and I mourn the  loss of its unique way of being in the world. When I look at the passenger pigeon, I recognize and mourn the loss of its entire species’ unique way of being in the world. And I sit with my grief, accepting that death is the last refuge where the truth can simply offer itself without provoking the impulse to undo it, where I can let things be and accept that it’s not all about me and my species. That is loss, that is grief, and that is love.

***

– end notes –

* Killing, whether for food or sport, is a trait humans share with many organisms. Humans are, however, the only species (or mammals, at least) who capture, cage and keep their captives alive. (There are probably insects and fungi out there who capture and keep other specie, like ants farm aphids. If you know of any others, let me know.)

** If you would like to read more about our conversations about death, read here, here and here.

Nadia stood before that same pigeon and also a big eagle, and the other really old exhibits that were meant to be a historical exhibit, rather than a natural one. She was horribly offended by ‘real’ things in the museum, thinking hunters had killed them for science. We talked a lot about the need to study things, and learn and understand, but also to leave things untouched, because we are wont to introduce harm…. difficult conversations!