I got Christopher Alexander(et.al.)’s A Pattern Language from the library a few days back and am just blown away by it. This man had such humble, democratic insights into the task of the architect and a real feel for natural, beautiful,  human and humane living spaces. His book first proposes patterns for building cities, towns, neighborhoods. About the latter, we writes:

14. People need an identifiable spatial unit to belong to.

You can see that I devoured this because there is so much there for the Transition worker. Then it continues on to groups of buildings, houses and gardens, rooms (indoor and outdoor), alcoves, seats… smaller and smaller. Here’s one of my favorite patterns, one that, now that I have tended the fire for over three year, makes me nod and smile:

181. The Fire: There is no substitute for fire.

Alexander stresses the communal aspect of fire as he does for all his patterns. The patterns are always in service of people-living-together, whether in towns, neighborhoods, houses, room and gardens. It is about people of all ages, communing, playing, celebrating, working and learning together, letting each other into their lives and homes, and about the privacy and solitude that a social human being also craves. Another favorite,

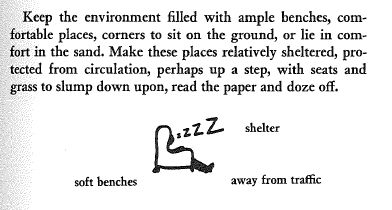

94. Sleeping in public: It is a mark of success in a park, public lobby or a porch, when people can come there and fall asleep.

(A friend remarked that this is what gets you arrested these days, “for breathing while homeless,” then asked if he should get off his soap box. I said: “If your soap box isn’t comfortable enough to sleep on/in…”)

It’s no wonder that this Pattern Language is used in Permaculture design: it is all about niches for humans in society, built environments and nature, with a minimum of competition and a maximum of cooperation and joy. Published in 1977, the book is at times old-fashioned when it deals with materials and technologies, but it is for the most part timeless. And as an object it feels good: heavy in a handy way, 1171 thin, crackling pages, like a Bible, or the Kritik der reinen Vernunft, and of course I got it for my library. This website has all the patterns in their sequence if you want to explore.

0000

What I am most interested in at this point is invitations. How do you make a place inviting to potential visitors and even to the people who live there? That someone owns a place or works in one, that he walks in and out every day, doesn’t automatically mean they were invited in. The majority of buildings we live and work in are dead to some degree that no rugs or framed prints can make them alive. What to do with these buildings that already exist?

Alexander’s architecture is democratic: he wants the average person to be able to build, and rebuild.  His solutions are small ones, though they are not to be confused with easy ones, like the facile throw of a rug or the hanging whatever print is trendy – for those, consult Cosmopolitan or Martha Stewart. Alexander’s solution do require work, that is, thought and labor.  Raising pillars, creating ceiling vaults (with burlap!) and building bed nooks require tools (hammers, nails, hands), resources and some handiness. And often times it is clear that he takes it for granted that one person can’t do this: to reclaim our buildings from cheap functionality or cold self-aggrandizing, it takes a village…

There are some good things about our 1200 sq.f. 1950s ranch: it’s small and compact and by some lucky stroke it faces mostly south and the chimney runs down the middle of the house. But it’s so boxy and straight! I marvel at the lack of organic fluidity – no wonder I love my pudgy wood stove with its rounded corners. Slowly I will start working on this, rounding my house. But first, I want to make it more inviting.

00000

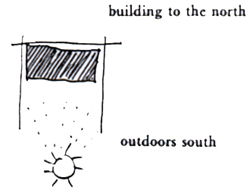

105. South Facing Outdoors:Â People use open space if it is sunny, and do not use it if it isn’t, in all but desert climates.

This is perhaps the most important single fact about a building. If the building is placed right, the building and its garden will be happy places full of activity and laughter. If it is done wrong, then all the attention in the world, and the most beautiful details, will not prevent it from being a silent gloomy place. […]Â Always place buildings to the north of the outdoor spaces that go with them, and keep the outdoor spaces to the south. Never leave a deep band of shade between the building and the sunny part of the outdoors.

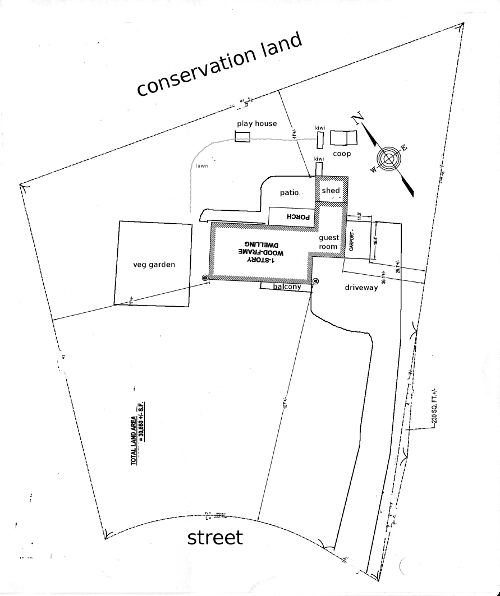

We do well by this pattern. Our house faces more or less south and it has a large stretch of land in front of it. We have a large stretch in the back as well and that is sunny too, since we have only a one story house which doesn’t cast much shade.

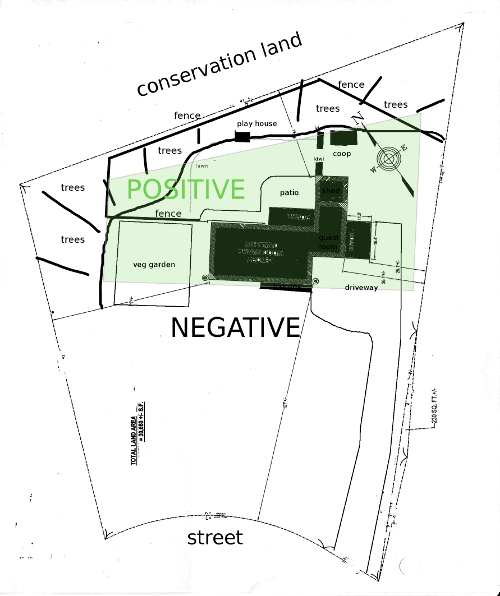

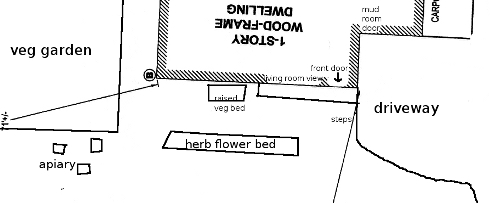

Nevertheless my observation over the last four years is that we hang out almost exclusively in the back. In the back is the screened-in porch (where we sometimes eat dinner), the paved  patio (more meals under the umbrella, grilling, and summer carpentry work), the small lawn (ripped up by too much badminton) and beyond that, at the edge of the trees, Amie’s play house. To the right is the shed and the kiwi trellis, which invites you to the chicken coop and the wood piles in the east. To the left, in the welcome shade and between the rampant hostas, are the rain barrels, and then, around the corner of the house  lies the vegetable garden to the west. All around the edge of all this activity is a rim of towering, mature oak and pine. Beyond our property line in the north there is a narrow wooded stretch of conservation land and then it goes down the wooded hill. We spot the lights of our neighbors down there only in winter when the trees are leafless.

All our outdoor activity then, all our play, work and food, happens in back. Â None of it up front. When we come up from the street, either walking or driving up the driveway, we head inside or around back immediately. Most plants grown up front get watered last or are downright neglected. The two rain barrels I had up front are used last. I’ve written about the challenge of this area before.

view south-west from our living room window

When it’s warm we keep the “official” front door from our balcony straight into our living room open, but that and this view out the window is about all the interaction we have with that huge stretch of property south of us. Why is that? Â It has to do, in part, with pattern 106.

00000

106. Outdoor spaces which are merely “left over” between buildings will, in general, not be used.

There are two fundamentally different kinds of outdoor space: negative space and positive space. Outdoor space is negative when it is shapeless, the residue left behind when buildings – which are generally viewed as positive – are placed on the land. An outdoor space is positive when it has a distinct and definite shape, as definite as the shape of a room, and when its shape is as important as the shapes of the buildings which surround it. Â […] Negative spaces are so poorly defined that you cannot really tell where their boundaries are, and to the extent that you can tell, the shapes are nonconvex. […]Â Make all the outdoor spaces which surround and lie between buildings positive. Give each some degree of enclosure; surround each space with wings of buildings, trees hedges, arcades and trellised walks, until it becomes an entity with a positive quality and does not spill out indefinitely around corners.

All the positive space on our property is behind the house, where one has a feeling of safe and well-defined enclosure by shed, planters and trellis, treeline and fence lined by berry bushes. The space in the front of the house on the contrary is ill-defined.

Upon approach up the driveway a large asphalt circle opens up with to the left the bisection of the property by the long, straight length of the house. Turn west and in front of the house is an open space hardly dissected by an amorphous medicinal flower bed, a weedy slope downward with toward more weeds, some trees along side. The only things that draw your eye when you’re up near the front are the three beehive boxes to the west.

When you look up at our house on the hill from the street the negative aspect of this space is even more evident:

It looks better in Spring, like this:

Still, this picture is a case in point, as the only time we actually get to enjoy this view is when we walk down there to take a picture. The solution, then, is to turn all this wasted space into positive space by giving it more definition, by dividing it up and enclosing it with soft edges punctured with inviting gateways and entrances. How we’ll do that involves some more patterns.

Leave a comment