After taking some pictures of her beautiful feathers and her dinosaur feet, we returned Nocty to the Earth today.

Be joyful though you have considered all the facts

Our plans to bury the recently deceased Nocty were thwarted by the deep freeze we are in. The ground is rock hard. The bird too.

I put Nocty in an empty feed bag and rolled it up. I’m keeping her on the porch so no big animals can get at her. As for the little ones, the undertakers, they won’t start their work until the body defrosts. Amie asked why, and I explained we humans are about 60% water and I suspect it’s somewhat similar for a chicken. She got it right away with regard to the chicken. It blew her mind that the same goes for the soil. I couldn’t say how much water is in the soil, but all the tiny spaces between the mineral molecules were flooded when it rained or when the snow on top of it melted, and then that water too froze. So the soil per se isn’t frozen, but the water that saturates it is. That’s why my shovel can’t make a dent in it.

Thinking of it now the similarities between the state of the bird and the state of the soil go further. Both seem brittle, parched, dry, because the water in them can’t do its thing, that is, moisten and move.  The soil should be awash with life and so should Nocty – Amie believes that firmly now, that Nocty should rot and give her body back to the circle. But the bird, the creatures who will do the rotting (the washing), and the medium in which this can be done (the soil/the water) – all are waiting.

Looking down into the brown paper bag at the golden brown feathers, it doesn’t feel right that she’s neither alive in the chicken-sense, nor in the rot-sense. I hope we’ll have a thaw soon.

After reading Lauren Scheuer’s book, Once Upon a Flock, in one swoop, Amie now has a favorite blog: Scratch and Peck, which is adorable and very funny and, well, about chickens! She has decided that this Spring we should get one Barred Plymouth Rock, one Black Australorp, and one Buff Orpington, just like Ms. Scheuer has!

Today, just now, in fact, four us met to talk about “inner work”. The question was: what do we need? Not just us, but our community. We talked about how we often feel judged and marginalized simply because we voice our doubts, fear, grief, helplessness. About how there must be others in our towns, struggling with these feelings, but alone. They might think that there is a problem with them, that it’s depression. But, as Jenkinson says, “what if there is nothing wrong with you?” What if it’s not their psychological problem, but a whole community’s cultural problem? What if what you’re feeling is not depression, but grief, and you have a perfectly good reason for that grief? What if we as a group started speaking a bit more openly about our grief, owning it, valuing it? What if we started building a whole new culture. We might create a space where people can come and talk, a safe room like Francis Weller describes, with a floor where we can stand with our grief and not feel like we’re in free fall. More organically, a place and community, in nature where we belong, where grief can enrich us and blossom along with its sister, joy.

Yes.

I’m so glad I picked up Barbara Hurd’s books, Stirring the Mud and Entering the Stone. I’ve started reading the first one and was hooked as of page one. She alerted me to the wetlands, bogs and marshes, and the marginal areas, high-traffic, super-diverse, home to species of the two biota that overlap there, as well as to “edge species”. Humans, she points out, are not such an edge species. We don’t feel comfortable in the undefined, not-one-or-the-other places. We don’t like to be on edge.

I like the idea of the edge. We’re not talking the kind of place where one thing stops and something else begins, a clear edge like a cliff, or the horizon, or the doorstep where indoors becomes outdoors. We’re talking of two edges in fact, in the case of the wetland, the edge of the land, and the edge of the wet,and an overlap, where it’s both wet and land. A nest of being, being-neither and being-both.

Can we think of ourselves in such a place? In between two stories, in both stories, and in neither, all at the same time. We are undefinable. Saints and hypocrites and average human beings in the twenty-first century. Let’s put others on edge. Everyone who thinks they know where they are, in terra cognita, when they’re with us and we’re at our best (with our talk of grief and danger and immeasurable joy)Â will suddenly find they have wet feet!

I also read, in Paul Shepard, that the ferocity of territorial species is highest in the very heart of their territory, and less on the edges, where the work is one of balancing territoriality with sociality, security with vulnerability. On the edges of the territory are the common spaces. This should give us courage. There is a way of being on edge together. We may have forgotten it – we who have paved over the wetlands, colonized the whole world into one territory, retreated deeply inward via the internet and psychotherapy – but that is our culture‘s error. We know that deep inside we are still human. Let us learn again the way of the edges, where give means take, take means give – one wild and fecund circle!

Next time remind me not to go in. Definitely, if I do go in, not to visit the Nature section. And if I get there anyway, not to listen to Amie!

She had checked out the Children’s section already and found nothing of interest. Then she joined me in front of Nature – I don’t think she’ll ever go back to Children’s. It’s only two cases, so she read title by title, calling them out to me – siren song! We were no better than each other. We spurred each other on. It’s the fault of neither one of us.

Amie chose chicken and goat books:

I chose the following (bear in mind that the word “choose” is sued here in a loose sense):

PS. We did not get to bury Nocty. Both ground and chicken are frozen.

Amie took the news of Nocty’s demise very well, much better than I thought she would. She was shocked, then cried a little. After absorbing the news, we went to see the body on the porch. It was dark so I brought a flash light. I lifted the cardboard to uncover the body and Amie stroked Nocty’s  soft feathers. She said, “She is still a beautiful bird.” Then she became very curious. She tried to open the wing, remarked on the stiffness and I explained that when the blood is no longer flowing, the muscles get stuck and stiff. She even peeled open the bird’s eyelid and peered into the eye, searching for something.  I didn’t ask or talk, wanted to let her thoughts be free.

Amie took the news of Nocty’s demise very well, much better than I thought she would. She was shocked, then cried a little. After absorbing the news, we went to see the body on the porch. It was dark so I brought a flash light. I lifted the cardboard to uncover the body and Amie stroked Nocty’s  soft feathers. She said, “She is still a beautiful bird.” Then she became very curious. She tried to open the wing, remarked on the stiffness and I explained that when the blood is no longer flowing, the muscles get stuck and stiff. She even peeled open the bird’s eyelid and peered into the eye, searching for something.  I didn’t ask or talk, wanted to let her thoughts be free.

Then we went to check on Oreo, Nocty’s “sister,” who is now alone at the mercy of the older hens. The chickens were roosting, so she didn’t get to talk to Oreo, but this morning she went out to the coop before school and sat with her for a while. Her abiding concern, as mine, is with Oreo.

She also asked if we could keep Nocty the way she is and I explained we couldn’t, that she will rot. I explained that rotting is  being returned to the flow, that specialized insects and bacteria go in and tear down all the bonds that bind the flesh together and so release the atoms back into the stream and so on, into other bodies and new life.  I said to let that happen we should bury her, put her into the Earth, and we discussed where on the land. I proposed one of the garden beds. Then Nocty’s atoms would go into the lettuces and we could eat them. Amie liked that a lot. Encouraged, I proposed that at the end of the season we could dig up the bones. She liked that too.

We have set Wednesday after school aside for Nocty’s burial. We’ll also  do research on whether it will be safe to eat those lettuces, and on how to preserve animal bones.

This morning I found Nocty, one of our younger Ameraucanas (she would have been a year old in April), dead in the coop. She was lying in the narrow space between the roost and the big door.  It couldn’t have happened long ago. Her blue egg was next to her, still somewhat warm. There was no blood or anything on her, and she didn’t freeze. There had been no symptoms, on the contrary, she was the energetic one, and she was regularly laying eggs. I think it may have been Sudden Death Syndrome, aka heart attack. I hope so, because I wouldn’t want there to be a disease in the coop. Everyone else seems fine, but then again, so did Nocty.

I was shocked and sad to see this sociable, sweet and funny chicken lying there so vulnerable and – I think this is what got me the most – so alone. She is still a beautiful chicken and I held her like she let herself be held in life, like a baby. Hardest of all is the realization that Amie will take it badly. Another issue is Nocty’s “sister” Oreo, who is at the bottom of the pecking order and who always found refuge with Nocty, who often pecked back at the four older hens.

It’s the first chicken we’ve lost, indeed the first pet (that’s how Amie thinks of her). I’m getting ready to tell Amie after she comes home and after her play date – which means I’ll need to keep mum the whole time they play. For once I hope it rains and they can’t go play outside, with the chickens.

On MLK day we went to the Boston Museum of Science with friends. We mostly hung out in the Green Wing with the New England birds and natural history displays. I enjoy studying the stuffed animal skins, the skeletons and fossils in their glass cases. No doubt some of my preference is due to the old-timey-ness, the absence of moving parts, sparks, recorded voices talking at you, and screens.  The MoS unfortunately does have  computer screens and games all over the place, and for this reason I prefer  the Harvard Museum of Natural History, specifically the upper floor, where the animals, frozen behind glass, are accompanied by small labels, often even just a number.

While most visitors over and under 8 were “interacting” with the screens, I came eye-to-eye with the American Robin (Turdus migratorius) and tried to understand why I am particularly attracted to these animal skins. It’s not like they look alive. The first thing we as eye-oriented animals seek in another is engagement with the eyes, and these eyes are invariably glass or plastic. They don’t fool us. In fact, the robin’s beady eye was like a bud from which the deadness blossomed to cover the entire animal.

The kids get this right away. One of the older girls (11) said she doesn’t like to see the stuffed animals because they’re dead and that’s “creepy”. She said she likes zoos instead. I offered that I don’t like zoos so much, because the wild animals are kept in cages and I think they might be unhappy. Another computer screen distracted her, so we didn’t get a chance to hash out this live-dead/free-caged/happy-unhappy tangle together. As for myself, I’d rather see a wild animal dead than caged and that’s because death is a natural state for a wild animal (eventually), but captivity isn’t*. I value life, so what attracts me then, in these stuffed bird skins, that I’d rather spend time with them than with their with living counterparts in zoos?

***

The same question from an another angle is this: what makes the skins different from skeletons? These birds are set up, not so that they look alive, but so that we can recognize them. These specimens get to stand in, quite convincingly, for their species, a class of animals we usually don’t see in their skeletal form when they’re tearing up our garden beds in search of juicy worms. As for the specimens of New England birds I don’t recognize because I’ve not seen them (yet), I try to memorize those, so that when I see the Northern Shrike in the wetlands next time, I’ll recognize it.

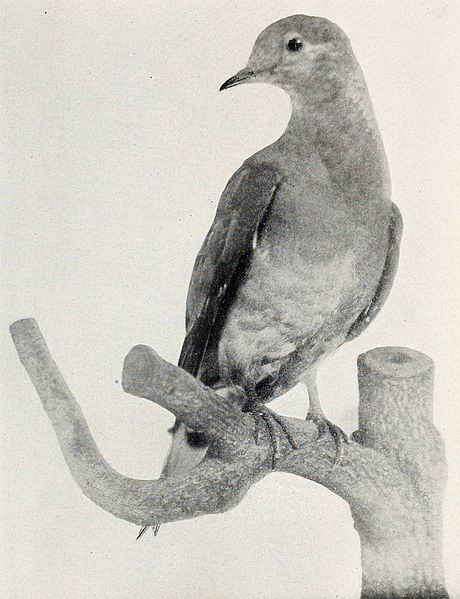

Is that the draw then, recognition? It’s part of it. To find what it is part of, there’s a test case, the case in the room that attracts me the most, the one with the extinct birds: the passenger pigeon (extinct since 1914) and, next to it, the heath hen (extinct since 1932). I look at them and part of what happens is recognition: in the passenger pigeon, I recognize the mourning dove that visits my feeders every spring. But something more happens…

Extinct. Steward Brand (TED talk) says that “extinction is a different kind of death. It’s bigger.” Who ever heard of such a thing? Let’s ask the children. Amie, when she was two-and-a-half, had repeated nightmares about a dinosaur. She woke up screaming and often would refuse to close her eyes again, because there was a dinosaur in the room, or it was coming. One evening we told her that the dinosaurs are dead. It was her first conversation about death**.

– What’s ‘dead’?

– Dead means the dinosaur can’t move, can’t walk. Dead means he can’t talk, or listen, or look. Dead means his body is lying in the ground somewhere, buried, often even crushed to pieces. So he can’t get up and come here.

– But this dinosaur isn’t dead.

– That’s not possible. All dinosaurs are dead. That’s why we name them with a special word: ‘extinct’. ‘Extinct’ means that all the dinosaurs, without exception, are dead. So no dinosaur can come here.

It was that simple:  Amie’s nightmares stopped. So clearly, extinction is a matter of quality (something different), not quantity (not just “bigger”). What makes the passenger pigeon skin different from the robin’s or the shrike’s skins might just illuminate my attraction to these bird skins.

***

Back at the museum, DH mentioned that scientists are very close to cloning or genetically manufacturing the passenger pigeon. This is called “de-extinction” and Steward Brand’s organization, Revive and Restore, mentioned in my last post, is a big part of that project. Well, I said to DH, these “revived” pigeons, they would die of fright and heartbreak. It is as for the insect egg that lies a hundred years in the soil, that by the perfect circumstance of light and temperature and humidity and ripeness bursts into life, only to find that all the plants it feeds on are long gone.

I’ll not go into my problems with Brand’s essay, “Why revive extinct species,† which reeks of smokescreens. I’ll just evoke Martha, the passenger pigeon, who was bred into captivity in 1885 in the Cincinnati Zoo, where she died, the last of her species, in 1914. Did she feel lonely? I don’t know, but for a bird that evolved and lived in flocks of over hundreds of millions of birds, her life was at the very least as unnatural as its gets, in zoos.

With Brand’s first “new” bird, we’d be back to that situation.  But, Brand and his colleagues rejoice, not for long! What happened in the past – start with five billion passenger pigeons, hunt them so there are less and less of them, down to one, then none – will be reversed - they’ll be one, then more and more and so on, one presumes, to five billion again (?).

All is reduced to quantities (extinction is a “bigger death”) and after that easily reversed simply by adding something on the other side of the equation. Nature and evolution did the work at the left side, now man will do the work on the right side. Together, they will equalize to nothing. Something will be undone. I want to stress that, that de-extinction is not about adding anything to the world, but about cancelling out, undoing something.

Undoing what? Here’s Brand, in his TED talk, asking how extinction at our hands should make us feel: “Sorrow, anger, mourning? Don’t mourn, organize.â€

Mourning is the experience of loss, a relearning of ourselves in a world where something is missing. We don’t mourn the death of a loved one, or the extinction of a species, we don’t even mourn them. We mourn their absence in our world. That is what brings us grief. Brand’s denial of mourning is therefore absolute, for he denies even the loss itself: we will not have lost, he says, it will no longer be missing.  We don’t have to mourn, we just have to make it like it never happened.

How does this reflect in the light of a story told by Weller, in the talk I referred to in my last post, of a man who asked him how he can be done with the grief for his deceased wife? Weller answers that he can’t: “This is your new relationship with your wife. This is the evidence that you chose to love.”

***

The 11-year-old who find that room at the Museum of Science “creepy” because it is full of death, gets it. The room is full of death and that is why I like it there. Because when I look at the American Robin with the plastic beads for eyes, I recognize Turdus migratorius as well as the fact that it’s dead, and I mourn the  loss of its unique way of being in the world. When I look at the passenger pigeon, I recognize and mourn the loss of its entire species’ unique way of being in the world. And I sit with my grief, accepting that death is the last refuge where the truth can simply offer itself without provoking the impulse to undo it, where I can let things be and accept that it’s not all about me and my species. That is loss, that is grief, and that is love.

***

– end notes –

* Killing, whether for food or sport, is a trait humans share with many organisms. Humans are, however, the only species (or mammals, at least) who capture, cage and keep their captives alive. (There are probably insects and fungi out there who capture and keep other specie, like ants farm aphids. If you know of any others, let me know.)

** If you would like to read more about our conversations about death, read here, here and here.

{The following is an offshoot and distraction from another, much more difficult post, which can be read here.}

Via my studies of Stephen Jenkinson I found this talk on grief by Francis Weller,  In it, Weller likens the history of mankind to a 100 foot long rope. The first 99 feet represents humans in nature, hunting, foraging, defending themselves, making fires and clans. The last 10 inches represents agriculture, the last 3/4 inches the industrial age, and the last sliver, the information age. That sliver we call  “normal”  and by doing so, we  condemn ourselves to homelessness and deep, deep grief. The talk is full of gems and I suggest you listen to the whole thing.

Weller quotes Paul Shepard, whose fascinating book, Man in the Landscape, poses two theses that I find plausible and helpful. The first is that there is still, inevitably, a huge presence of that nomadic caveman, that hunter-gatherer in our primitive brains, in our very bodies. Even deeper:

The genes’…. environment extends from the immediate nucleoplasm surrounding them in the cell to the distant stars. It ranges from the colloids and membranes upon which they float to the light from the sun and croaking of frogs.

and

The idea of “remembering” our life in the trees does not mean recollecting a stream of day-to-day events. The human organism is its own remembering. The emergence of the past into consciousness is inseparable from awareness of ourselves.

Then, not allowing ourselves to engage that part of our identity – by not even making the movements that have kept us alive for millions of years, like throwing a spear or making a fire -Â we are starving our bodies, our minds, our culture, our world.

My sense is that people like me are ecologically bored, that we possess the psychological equipment required to navigate a world that is far more challenging than our own—a world of horns and tusks and fangs and claws. Yet our lives have been reduced to the point at which loading the dishwasher seems to present an interesting challenge…  I think all of us have a sense that we’re not quite fulfilling our potential as the human beings who evolved in this really quite thrilling and exciting and dangerous environment, and that our lives are a bit too small and too constrained.

That night, in that hot cave, I dreamed deeply. In the dream,

On a warm and sunny day last week, Â I let the chickens out in the yard. Amie came home from school just then and she joined the flock. For an hour she herded the hens around, nattering and scolding like a mama hen, with some marvelous life lessons (for chickens). What is the difference between needs and wants? She explained it to them. It is thus: If you need something but you don’t want it, it’s always a mistake. If you want something that you don’t need, it could be a mistake. It depends. Luckily, for chickens the factors aren’t too complex. In the end the chickens ran back into the coop out of their own volition, knowing full well what they needed.

Most of the snow melted.

Yesterday a snowstorm blew in and dumped a lot of wet, thick snow. The land is transformed again. The clouds above are fat and fast.